Mientras padecemos una severa gripe ABC1, y prácticamente nos hacemos entender por señas, violamos una de las reglas del blog, que es no escribir cosas en otros idiomas sin traducir, y vamos a mantener la continuidad del blog apoyandonos en nuestro amigo el escáner.

Se ha escrito mucho, y tal vez lo haremos, sobre Sonia Sotomayor, a quien Obama nominó para la Corte Suprema.

Mientras tanto, en el hospital de campaña leemos "The Nine", una especie de "Hacer la Corte" que cuenta detalles de los últimos años de la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos, básicamente entre 1999 y 2006, con flashbacks muy ilustrativos. Es un libro de 2007, muy amable y de prosa ligera, algo de chisme, no es una obra de jurisprudencia. Literatura de aeropuerto, muy recomendable tanto para los que están en el tema como para los que no conocen mucho el ambiente. Está escrito por Jeffrey Tobin.

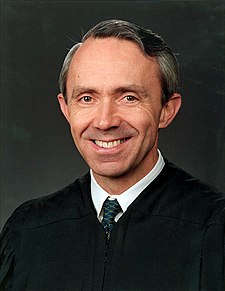

De ahí sacamos tres perlas de David Souter, precisamente el juez que acaba de renunciar, dejando la vacante que Sotomayor ocupará.

Cosas para decir en una primera cita

A Souter, un solterón -una vez elegido entre los diez solteros más codiciados por el Washington Post- sus compañeros lo querían casar. Miren cómo les fue.

O'Connor had a more direct agenda with Souter. She wanted to get him married off. (...) Over the years, practically everyone Souter knew in Washington, including First Lady Barbara Bush, tried to fix him up. None succeeded. One of his fellow justices once prevailed on Souter to take a woman out to dinner, and she reported back that she thought the evening had gone very well —until the end. Souter took her home, told her what a good time he had, then added: "Let's do this again next year."

Souter sobre la tarea de juzgar.

Resulta que en 2002 murió Gerald Gunther, que había escrito una biografía del Juez Learned Hand, el campeón sin corona (the greatest judge to never sit on the Supreme Court) que era uno de los modelos de Souter. Souter habló en el funeral:

Souter's eulogy praised Gunther and Hand, but it really amounted to a short essay about "what anyone's judging ought to be." Hand had served from 1924 to 1961 on the federal court of appeals in New York, where his views resembled those of the modérate, careful jurisprudence of his friend John Marshall Harían II, who was Souter's other judicial hero. Souter spoke of "every judge's common obligations: suspicíon of easy cases, skepticism about clear-edged categoríes, modesty in the face of precedent, candor in playing one worthy princíple against another, and the nerve to do it ín concrete circumstances on an open page." This was autobiography for David Souter, the cautious guardian of the right to privacy, the fierce advócate of strong national government (and unrelenting foe of Rehnquist on federalism), the painstaking, even slow, judicial craftsman.

Souter, escribiendo el voto de Grokster v. MGM.

Un dinosaurio que no tiene celular, que no sabe usar un fax. Una vez el senador Rudman -gran amigo- le regaló un televisor, que fue el primero de su vida. Aparentemente, Souter nunca lo enchufó.

Ese tipo, resolviendo -bien- un caso complejo de tecnología y mainstream media.

The case that summed up Souter's achievement as a justice vfif one that was argued and decided during Rehnquist's illness. Thd issue in MGM f. Grokster concerned one of the most vexed issues in copyright law—whether the maker of software that can be used for copyright infringement shouíd be held Hable if its produce is in fact used that way. Billions of dollars were at stake in the case becauseI virtually all video and audio entertainment can be illegally copiedj and distributed on software like Grokster. Would rulíng for the I software maker condemn movie studios to wanton piracy? Would 1 ruling for the studio stifle technological innovation? Before the case was heard, it was widely predicted that the Court would split in the face of those difficult questions and make the law even more complicated than it already was. But Souter managed to unite the Court behind his opinión, which held that software makers could be liable I only if they took affirmative steps to encourage infringement. It was a largely apolitical decisión that managed to draw support from left and right, creators of entertainment and distributors of it, artists and entrepreneurs —and it was written by a man who worked I exclusively with a fountain pen. Souter's opinión showed a sophistícated understanding of the markets for both technology and entertainment —from a man who only in 2003, while presiding over a wedding, learned the name of a singing group that was more than liimiliar to his colleagues, the Supremes.===

- Souter, de 69 años, entró a la Corte Suprema en 1990, nominado por Bush padre.

- Compré The Nine por alibris, me costó 3 dólares y (aprox) 20 dólares el envío. Acá, la crítica del NYT.