Después de la antología arbitraria del año catorce del post anterior, esta es nuestra selección de los mejores papers y artículos de la academia norteamericana de teoría del derecho y afines de 2014. Van links a los artículos completos, seguidos del abstract respectivo.

Obviamente, esta es una lista escogida (y variopinta: hay derecho privado, público, penal, etc.) de lo que leímos (posiblemente, unos 60 o 70). Al final elegimos los muy recomendados y hay una yapa que busca vindicar a los abogados. Si tienen alguna sugerencia, notificad en los comments.

There Is Nothing that Interpretation Just Is (Cass Sunstein)

How Behavioral Economics Trims Its Sails and Why (Ryan Bubb & Richard H. Pildes, artículo que puede leerse en conjunto con A Psychological Account of Consent to Fine Print de Tess Wilkinson‐Ryan, también de 2014)

Misreading like a lawyer (Jill C. Anderson)

Fighting legal innumeracy (Edward K. Cheng).

Criminal Attempts (Gideon Yaffe)

What 30 Years of Chevron Teach Us About the Rest of Statutory Interpretation (Abbe R. Gluck)

Rules Against Rulification (Michael Coenen)

Narrowing Precedent in the Supreme Court (Richard M. Re) (recomendado cum laude)

Disappearing Claims and the Erosion of Public Law (Maria Glover) (recomendado magna cum laude)

----

Posdata Nos queda, de yapa, uno de 2013 que nos recomendó Mark Healey Parera. No es verdad que haya demasiados abogados.

- The Lawyer-Rent Seeker Myth and Public Policy (Teresa J. Schmid).

Obviamente, esta es una lista escogida (y variopinta: hay derecho privado, público, penal, etc.) de lo que leímos (posiblemente, unos 60 o 70). Al final elegimos los muy recomendados y hay una yapa que busca vindicar a los abogados. Si tienen alguna sugerencia, notificad en los comments.

|

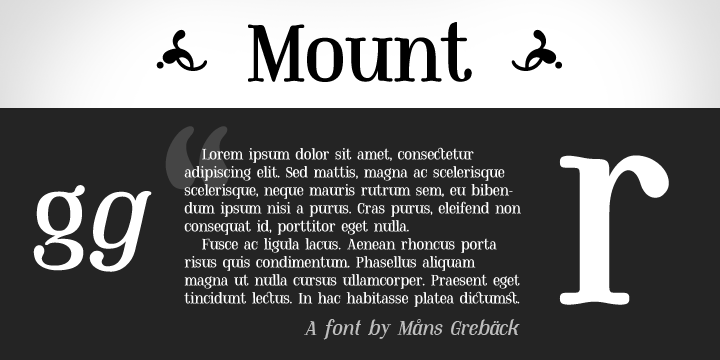

| Fuente: Mount |

There Is Nothing that Interpretation Just Is (Cass Sunstein)

Some people believe that the very idea of interpretation requires judges to adopt a particular method for interpreting the Constitution. The problem with this view is that in constitutional law, the general idea of interpretation is compatible with a range of different approaches, and among them, none is mandatory, in the sense of having some unique or privileged connection with the general idea. Any particular approach must be defended on the ground that it would make our constitutional order better rather than worse. No one should doubt that there are legitimate questions about the institutional capacities of judges, and about the virtues and vices of a deferential role on their part; the answers to those questions can motivate a view about constitutional interpretation. But they do not depend on an understanding of what interpretation necessarily requires.

How Behavioral Economics Trims Its Sails and Why (Ryan Bubb & Richard H. Pildes, artículo que puede leerse en conjunto con A Psychological Account of Consent to Fine Print de Tess Wilkinson‐Ryan, también de 2014)

The preference of behavioral law and economics (BLE) for regulatory approaches that preserve “freedom of choice” has led to incomplete policy analysis and inefficient policies. BLE has been broadly regarded as among the most promising new developments in public policymaking theory and practice. As social science, BLE offers hope that better understanding of human behavior will provide a sounder foundation for policy design. As politics, BLE offers a possible political consensus built around minimalist forms of government action — “nudges” — that preserve freedom of choice. These two seductive dimensions of BLE are, however, in deep tension. Put simply, it would be surprising if the evidence documenting the failure of individual choice implied a turn toward regulatory tools that preserve individual choice.

Misreading like a lawyer (Jill C. Anderson)

Statutory interpretation dilemmas arise in all areas of law, where we often script them as scenes of conflict between a statute’s literal text and its animating purpose. This Article argues that, for an important class of disputes, this supposed discord between text and purpose is an illusion. In fact, lawyers are overlooking ambiguities of literal meaning that align well with statutory purpose.

It then turns to the question of why lawyers misread and what we can do about it. The converging literatures of language development and the psychology of reasoning suggest an answer. When we analyze opaque sentences explicitly as statutory interpretation requires (as opposed to spontaneously in conversation), we may be particularly vulnerable to cognitive bias. Factors peculiar to law tend to amplify and propagate this bias rather than dampen and contain it, but they may also point the way toward more sophisticated and reliable legal reading.

An old joke quips that lawyers go to law school precisely because they never liked math or were never good at math – and that therefore medical school (or these days, Wall Street) was not an option. While this tired joke may have a kernel of truth, I want to suggest that we should be very wary of internalizing it. Numeracy is a fundamental skill for any intelligent, engaged participant in society, and we lawyers ignore it at our peril.

Criminal Attempts (Gideon Yaffe)

The intuitive idea that failed attempts to complete crimes are often themselves crimes belies the complexity and confusion surrounding the adjudication of criminal attempts. This Article offers an account of the grounds for the criminalization of attempt that provides the courts with sorely needed substantive guidance about precisely which kinds of behavior constitute a criminal attempt. The Article focuses on three well-known problems in the adjudication of attempt that have been particularly baffling both to courts and to commentators: specifying the line between solicitation and attempt; determining the conditions under which an “impossible” attempt is still criminal; and identifying the relevance of abandonment to responsibility for and sentencing of attempts. The Article proposes specific doctrinal recommendations for adjudicating all three kinds of attempts; these recommendations are implied by the conceptual framework developed here for thinking about attempt.

What 30 Years of Chevron Teach Us About the Rest of Statutory Interpretation (Abbe R. Gluck)

Chevron, the most famous rule of administrative law, is also a central doctrine of statutory interpretation. But Chevron is understood and operates quite differently from most of the other statutory interpretation rules. This Essay explores six such divergences and how they illuminate of some the most important, unanswered questions of the statutory era.

Rules Against Rulification (Michael Coenen)

The Supreme Court often confronts the choice between bright-line rules and open-ended standards—a point well understood by commentators and the Court itself. Less well understood is a related choice that arises once the Court has opted for a standard over a rule: may lower courts develop subsidiary rules to facilitate their own application of the Supreme Court’s standard, or must they always apply that standard in its pure, un-“rulified” form? In several cases, spanning a range of legal contexts, the Court has endorsed the latter option, fortifying its first-order standards with second-order “rules against rulification.” Rules against rulification are a curious breed: they promote the use of standards, but only in a categorical, rule-like manner.

(...) Among other things, the Article points out that anti-rulification rules, while useful in some circumstances, can carry the surprisingly maximalist consequences of freezing the development of the law and constraining the methodological choices of lower court actors. In addition, the Article sets forth some prescriptive suggestions regarding the creation and detection of anti-rulification rules, proposing, for instance, that the Court should proceed cautiously before pronouncing rules against rulification and that lower courts should insist on express prohibitions from the Court before deeming themselves barred from the rulification endeavor.

Narrowing Precedent in the Supreme Court (Richard M. Re) (recomendado cum laude)

“Narrowing” occurs when a court declines to apply a precedent even though, in the court’s own view, the precedent is best read to apply. In recent years, the Roberts Court has endured withering criticism for narrowing in areas such as affirmative action, abortion, the exclusionary rule, campaign finance, and standing. This practice — often called “stealth overruling” — is widely condemned as deceptive, as well as contrary to stare decisis. On reflection, however, narrowing is not stealthy, tantamount to overruling, or even uncommon. Instead, narrowing is a distinctive feature of Supreme Court practice that has been accepted and employed by virtually every Justice. Besides promoting traditional stare decisis values like correctness, fidelity, and candor, legitimate narrowing represents the decisional-law analogue to the canon of constitutional avoidance. As a rule, an en banc appellate court, including the Supreme Court, engages in legitimate narrowing when it adopts a reasonable reading of precedent without contradicting background legal principles. Under this rule, most if not all instances of narrowing during the Roberts Court are readily defensible — including frequently overlooked decisions by the Court’s more liberal members. Moreover, prominent cases involving narrowing can be grouped into four categories: experimental narrowing, narrowing rules, narrowing to overrule, and aspirational narrowing. Far from being unusual or unwarranted, narrowing is a mainstay of Supreme Court practice — and a good thing, too.

Disappearing Claims and the Erosion of Public Law (Maria Glover) (recomendado magna cum laude)

The Supreme Court’s arbitration jurisprudence in the last five years represents the culmination of a three-decade long expansion of the use of private arbitration as an alternative to court adjudication in the resolution of disputes of virtually every type of justiciable claim. As scholars have traced, privatizing disputes that would otherwise be public may well erode public confidence in public institutions and the judicial process. Accordingly, many observers have linked this decades-long privatization of dispute resolution to an erosion of the public realm. In this piece I argue that the Court’s recent arbitration jurisprudence undermines the public law itself.

(.,.) Through the procedural device of private arbitration, private parties can effectively rewrite substantive law by precluding or severely impeding the assertion of certain types of civil claims. And they can do so almost entirely outside of public view, through commercial (and sometimes) confidential contracts subject to virtually no public scrutiny or regulatory oversight. In short, the Court has handed private parties the power to recalibrate substantive legal obligations, and because this power is largely unchecked, there is currently little to stop this erosion of public law.

Catalogs (Gideon Parchomovsky & Alex Stein) (recomendado summa cum laude, el mejor paper que hemos leído en mucho, mucho, tiempo, puede leerse en conjunto con The limits of enumeration de Richard Primus, también de este año)

It is a virtual axiom in the world of law that legal norms come in two prototypes: rules and standards. The accepted lore suggests that rules should be formulated to regulate recurrent and frequent behaviors, whose contours can be defined with sufficient precision. Standards, by contrast, should be employed to address complex, variegated, behaviors that require the weighing of multiple variables. (...) The Essay seeks to contribute to the jurisprudential literature by unveiling a new form of legal command: the catalog.

A catalog, as we define it, is a legal command comprising a specific enumeration of behaviors, prohibitions, or items that share a salient common denominator and a residual category — often denoted by the words “and the like” or “such as” — that empowers courts to add other unenumerated instances. We demonstrate that the catalog formation is often socially preferable to both rules and standards and can better enhance the foundational values of the legal system. In particular, catalogs are capable of providing certainty to actors at a lower cost than rules, while avoiding the costs of inconsistency and abuse of discretion inimical to standards. Moreover, the use of catalogs leads to a better institutional balance of powers between the legislator and the courts by preserving the integrity and autonomy of both institutions. We show that these results hold in a variety of legal contexts, including bankruptcy, torts, criminal law, intellectual property, constitutional law, and tax law — all discussed throughout the Essay.

Posdata Nos queda, de yapa, uno de 2013 que nos recomendó Mark Healey Parera. No es verdad que haya demasiados abogados.

- The Lawyer-Rent Seeker Myth and Public Policy (Teresa J. Schmid).

Two enduring fallacies in public policy are that lawyers are rent seekers who impair rather than stimulate the economy, and that there are too many of them. While lawyers may disagree with the first premise, they tacitly accept the second. These two fallacies have led leaders in both the political and professional arenas to adopt policies that impair access to justice. This study documents the negative effects of those policies and recommends courses of action to reverse those effects.